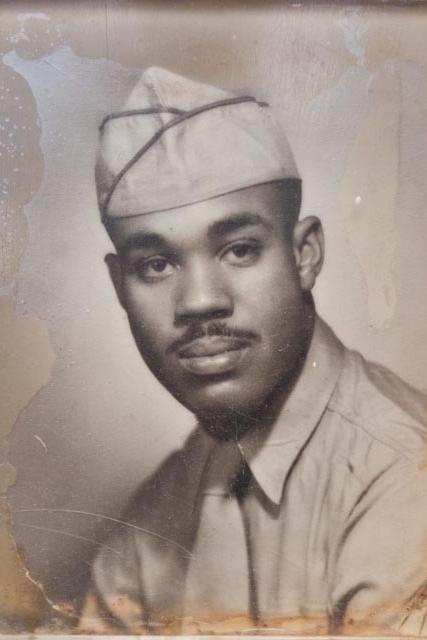

Theolus "B" Wells, one of the men featured in FORGOTTEN, passed away July 16. He was 96. Mr. Wells, 96, of Orangeburg, South Carolina, shared a foxhole on Utah Beach on D-Day. "I didn't have enough sense to be scared," he said, explaining that he was just a kid. During his time in Britain training for the invasion, he was often mistaken for the boxing champ Joe Louis. He didn't always correct the mistake, he said with a smile, especially if the person asking him happened to be a lady. You can read more about him here.

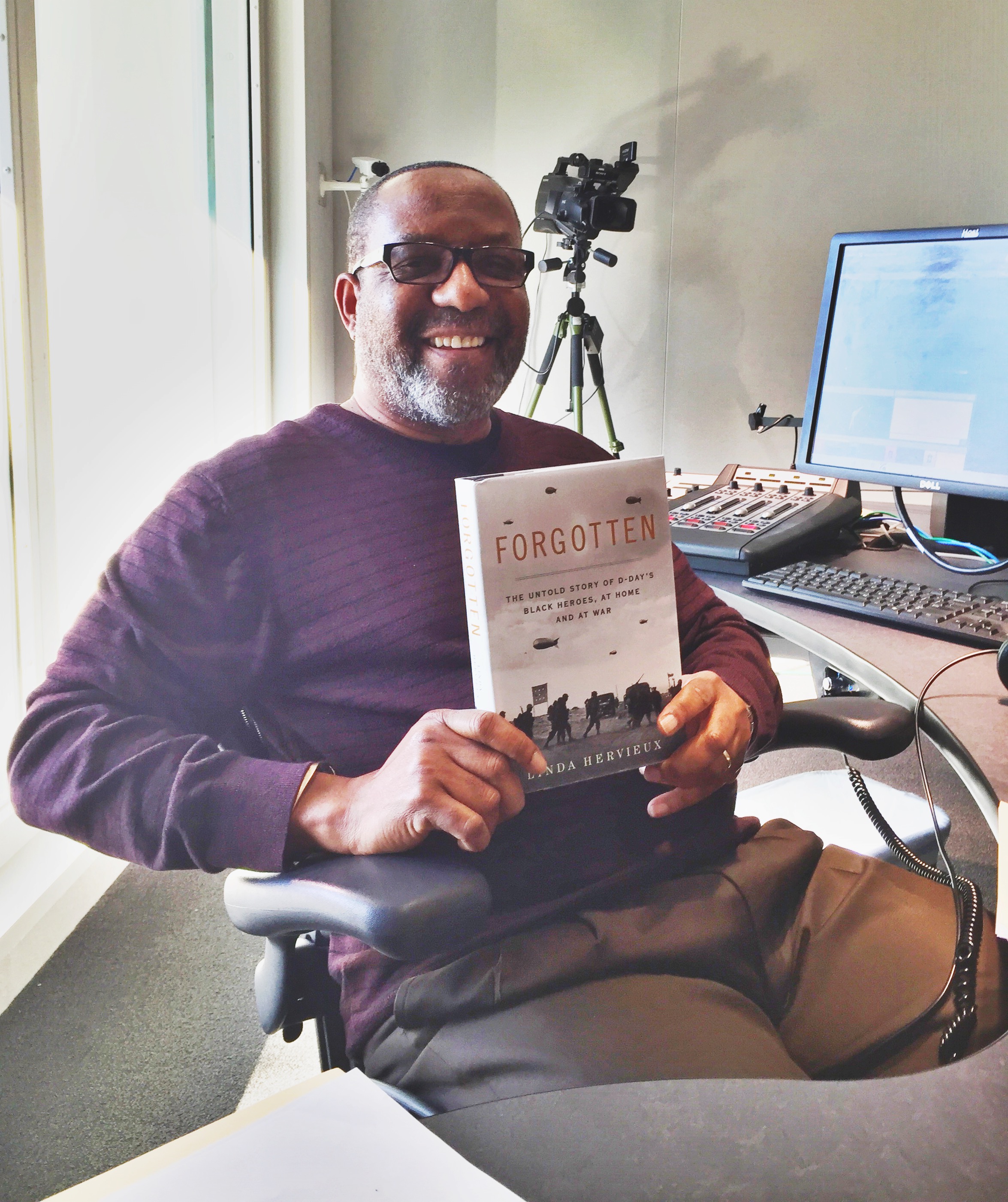

NPR's Here & Now features FORGOTTEN

The men of the HQ battery of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion pose in France, July 1944.

Thanks to NPR's Here & Now, recorded at WBUR in Boston, for inviting Linda Hervieux on the show to talk about FORGOTTEN: The Untold Story of D-Day's Black Heroes, At Home and At War. They also published an excerpt from the book. Read it here.

Veterans Day publicity blitz for FORGOTTEN

Linda Hervieux was joined by William and Beulah Dabney at the Harrison Museum of African American Culture in Roanoke, Va.

Veterans Day coverage of FORGOTTEN was overwhelming! The book made various TV, radio, print and websites. Linda Hervieux appeared with 320th veteran William Garfield Dabney in Roanoke, VA, on Nov. 10, to a full house at the Harrison Museum of African-American culture. On Nov. 11, she spoke at American University where she was joined by 320th vet Willie O. Howard and Joann Woodson, the wife of Waverly Woodson. The Woodson family has launched a campaign to obtain for him the Medal of Honor for his service on Omaha Beach.

See ABC7-TV's interview with Linda and Joann here.

ABC News reporter James Gordon Meek found a clip from Waverly Woodson's 1994 interview on the 50th anniversary of D-Day. See his report and video with Brian Ross here.

Hear Linda on the Kojo Nnamdi show on WAMU radio, Washington DC's NPR station here.

See Linda's interview on Bob Herbert's Op-Ed TV here.

See Linda's interview with NY1's Cheryl Wills here.

Richard Sisk at Military.com wrote up this piece on the Medal of Honor campaign, click here.

Linda snapped this iphone shot on the fly that hardly does justice to radio host Kojo Nnambdi, who was kind enough to invite Linda on his WAMU show to discuss the issues raised in FORGOTTEN. His producer said they got the most listener calls in recent memory.

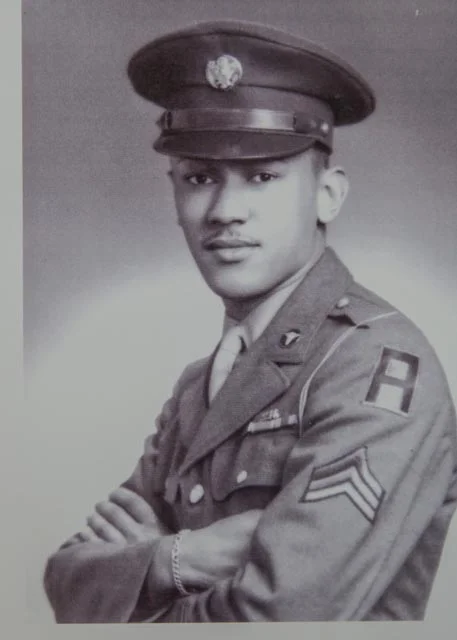

Meet Wilson Monk, a jack-of-all-trades from Atlantic City

Wilson Monk and Mertina Madison in 1941. The Monks were married for 68 years. "I love you more than yesterday," Wilson used to say.

It is June 1941. FORGOTTEN opens on the Atlantic City Boardwalk. Wilson Caldwell Monk is waiting tables at Heilig’s Restaurant, serving up platters of fresh lobster and stewed snapper to an endless parade of visitors. Monk and waiters like him are mostly African American. They are the descendants of southern migrants whose muscle and know-how helped build barren Absecon Island into America’s premier resort. As the nation inched toward another world war, black workers in Atlantic City were no longer welcome to share in the spoils of their labor. Amusement rides that were once open to all were now “whites only.” Segregation extended off the Boardwalk, with black families sidelined to a patch of sand that came to be known as “Chicken Bone Beach.”

When the draft letter came in the mail, Wilson Monk, 21 years old, saw an opportunity. It was a chance to land a secure job with decent pay. For the 12 months — he expected it to be a one-year commitment — he would serve in the U.S. Army, Monk wouldn’t have to worry about a paycheck. It would be a welcome reprieve. During "The Season,” the three months Atlantic City was open for business, Monk held down as many jobs as he could squeeze into a day. He mopped floors, delivered packages, sold salt water taffy and, of course, waited tables at fine restaurants that would never serve a meal to a black man like himself.

When the United States went to war in December 1941, Monk’s service was extended indefinitely. He would travel to Great Britain, where he would meet people like Jessie Prior, who taught him that segregation was not a natural state. Jessie was a devout Welsh woman living in a village called Abersychan. Jessie’s only child, 18-year-old Keith, was off at war. She would become a second mother to Wilson and her correspondence with his mother, Rosita, in New Jersey would continue for years after the young American with soft brown eyes and genteel manners left for the battlefields of France with his unit, the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion.

Before his arrival in Britain, Wilson Monk had never counted a white person as a friend. During his years training at an Army base in northwestern Tennessee, he had endured brutal racism. Despite his crisp Army uniform and sergeant stripes, his place on a train was in the “Negro car” hard by the dirty coal engine. He was denied a table in restaurants where German prisoners of war interned in America were welcome.

“Mrs. Monk, you have a son to treasure, and feel very proud of,” Jessie Prior wrote to Rosita Monk on May 3, 1944. “We love him very dearly, and will do anything in the world for him. … We have told him he can look upon our home as his home while in our country, and I will try to fill your place, if only in a small way … we shall look upon him now as our own.”

Read more about Wilson Monk in Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, At Home and At War, which goes on sale today. Click here to order.

To see more photos of Wilson Monk, click here.

To read more about Jessie Prior, click here.